I used to think that when people had children with severe disabilities, it would be something detected in the womb, or shortly after birth—that it would be obvious that something was wrong. But this was not at all the case with our son, Asa.

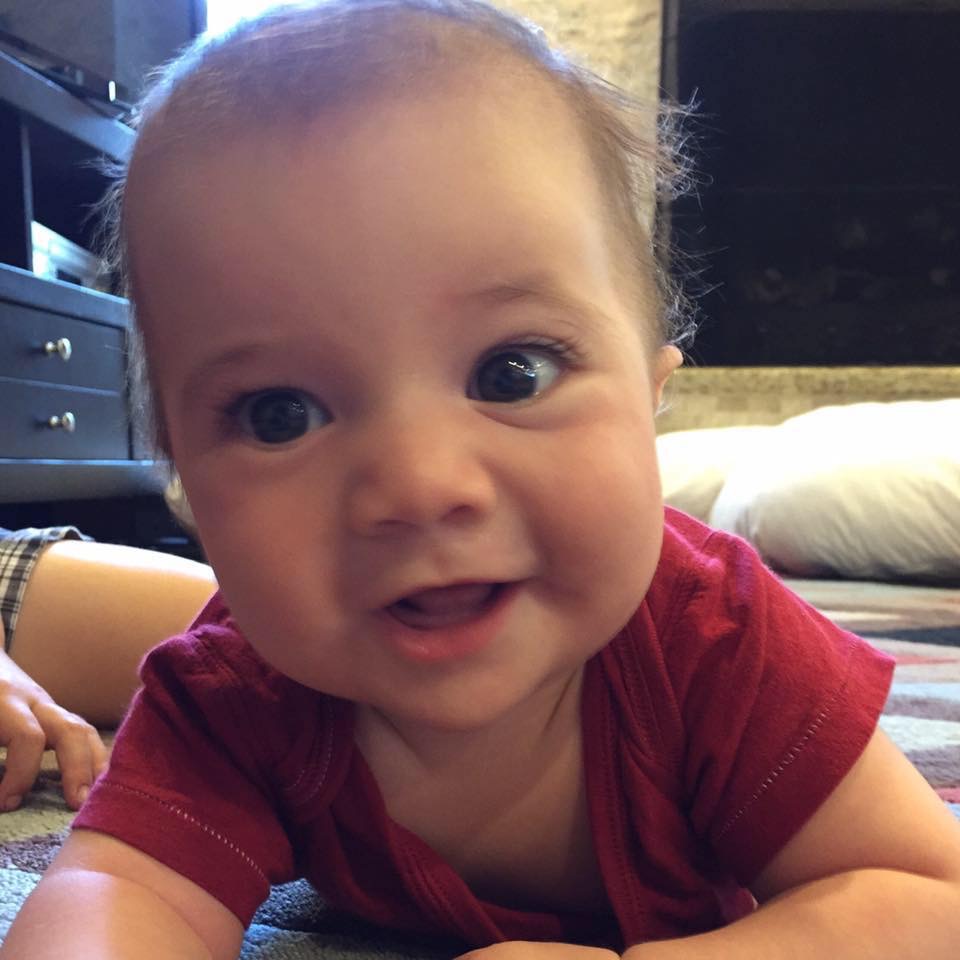

Asa is the third of three boys. He was born after a mere two hours of labor, a big healthy baby weighing 10lbs exactly. I remember a hospital staff member saying, “Congratulations—you have a toddler!”

For his entire first year of life, Asa developed almost entirely typically. He hit all his developmental milestones and was incredibly strong. The only indication of any problem was that he struggled to stay asleep, never really finding his Circadian rhythm. The sleep specialist said he didn’t see any reason he wouldn’t grow out of it. Asa walked on his first birthday.

But that soon began to change. Asa was developing differently from his older brothers. At fifteen months old, Asa still appeared as though he had just learned to walk the day before. He tripped over anything below his eye-level, never seeming to learn that he needed to look both down and forward as he walked. He had no comprehension that he had to walk differently down the stairs than on flat ground.

Around the same time, we noticed that Asa did not really seem to understand much language. He didn’t point to things or pay attention when we pointed to objects that weren’t directly in front of his face. His eye contact began to decrease.

He was diagnosed with global developmental delay.

I went online and completed the MCHAT assessment, which indicates likelihood of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in toddlers. The results said he was at moderate risk, so I contacted our pediatrician. She said she didn’t put much stock in these assessments before 18 months, and she wasn’t too concerned. But she went ahead and made a referral to the Texas Children’s autism clinic, because the wait lists for autism assessments are long—so long, in fact, that they involve a months-long wait list just to be contacted to *schedule* an appointment.

Over the next several months, our concerns worsened.

Every medical professional—and every resource I found online—strongly emphasized the importance of “early intervention,” so we wanted to get Asa started with physical therapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT), and speech therapy. However, actually getting these services proved difficult.

Early Childhood Intervention (ECI here in Texas) determined Asa was “too mobile” to get physical therapy—even though he had virtually zero safety awareness. And even though he clearly had serious deficits in language and communication, ECI declared Asa was “not verbal enough” to get speech therapy. ECI provided a bit of OT, but that was all.

Our private health insurance policy—a comparatively robust one—would not cover PT, OT, or speech for Asa, because it only covers “rehabilitative” therapies: if a child never develops certain skills in the first place, then therapy is only “habilitative”, not “RE-habilitative”. However, we managed to get some in-home PT and OT (as opposed to in-clinic) through some sort of loophole I will never understand, which was crucial in helping Asa with safety awareness.

Over the next few months, Asa made inconsistent progress. We made plans to enroll him in an expensive special needs preschool program, with the hope it would “catch him up” by Kindergarten age. He was diagnosed with global developmental delay (GDD). We finally got him evaluated for autism by two different doctors, and both diagnosed him with ASD at 22 months old. But no one told us Asa’s case was especially severe.

It was a massive regression.

Asa began the school program, and then we added ABA therapy (applied behavioral analysis). (The one good thing about our insurance plan is that it began covering ABA therapy for autism just one month before Asa was diagnosed with ASD). He was making progress—slow, but progress. He was imitating several sounds, and at 32 months old he said a couple of word approximations. Many of Asa’s autism symptoms were disappearing, and the BCBA—the professional who runs his ABA program—said she actually thought he might lose his autism diagnosis.

Things were going well…except for Asa’s sleep.

Because we believed Asa’s enlarged tonsils might have been contributing to his sleep problems, and we understood recovery to be easier at a younger age—we decided to go ahead with tonsil and adenoid surgery in March of 2018.

The surgery went fine…but it didn’t help Asa’s sleep.

And on the other side of the surgery, Asa never imitated a sound or made a word approximation ever again. He suddenly developed crippling anxiety and lost many skills he had gained.

It was a massive regression.

As if on cue, a couple of weeks later, we finally got the results of Asa’s final genetic test: whole exome sequencing, which we had pursued even though the geneticist advised it was not worthwhile. The test showed that Asa’s DNA has a single extra letter—in a very important place on a very important gene called SHANK3—causing a very rare and severe genetic disorder. At the time, there were fewer than 2,000 people diagnosed worldwide. There is no cure. There isn’t even any effective treatment.

[…] teaching Asa is like trying to teach a child who already has Alzheimer’s or dementia […]

Phelan-McDermid Syndrome—in Asa’s case, caused by that one extra letter out of three billion in the human genome—is causing his autism; intellectual disability; expressive and receptive language disorder; sleep disorder; hyperactivity and impulsivity; seizures; and pica (chewing and eating nonfood items).

One of the biggest tragedies is that no matter what progress Asa makes, it is *highly* likely he will have repeated regressions throughout his lifetime. Or if he doesn’t, he may always lose one skill as he learns another, like a reverse game of whack-a-mole.

This is because the SHANK3 gene is responsible for helping synapses to form between neurons in Asa’s brain. The best analogy I can make is this: teaching Asa is like trying to teach a child who already has Alzheimer’s or dementia: his brain doesn’t hold new connections together very well, and he also lacks the foundation of well-established neural pathways that most of us develop in childhood.

Another major concern is the possibility that Asa will develop worse and worse seizures. Some people with Phelan-McDermid Syndrome develop seizures that are so severe they are never controlled effectively.

Receiving and absorbing this news felt like we were watching a movie, which suddenly was rapidly rewound, flying backwards through the months, back to the day Asa was born—realizing that the expectations, hopes, and assumptions we had made about who he was, and who he might be, had all been completely wrong. All our photos of him—including one of then one-year-old Asa, grinning in a onesie that said “Future President”—seemed to mock our ignorance and innocence.

This news was nothing short of devastating for us. We had been pushing for therapies, pushing for genetic testing, pushing for answers. We had met obstacles at every turn and prevailed. But now this was a brick wall. There was no way to scale this wall.

We would have to live with it.